Written by Keita Funakawa COO & Cofounder of Nanome

I was at an LA networking event last month when a gentleman with a finance background asked. "So you work with molecules and stuff, right?" He leaned in with genuine curiosity. "What exactly are peptides?"

His colleagues nodded eagerly. They'd been hearing the buzzword everywhere: in wellness circles, from their longevity-focused friends, in earnings calls from pharmaceutical giants. They knew peptides were driving massive valuations. But they had no idea what they actually were.

So I started with etymology. Peptide comes from the Greek péptō (πέπτω), meaning to cook, to digest. The -ide suffix refers to the amide bonds that link amino acids together. A peptide is literally a chain of amino acids connected by these bonds, and the length of that chain determines almost everything about how it behaves in your body.

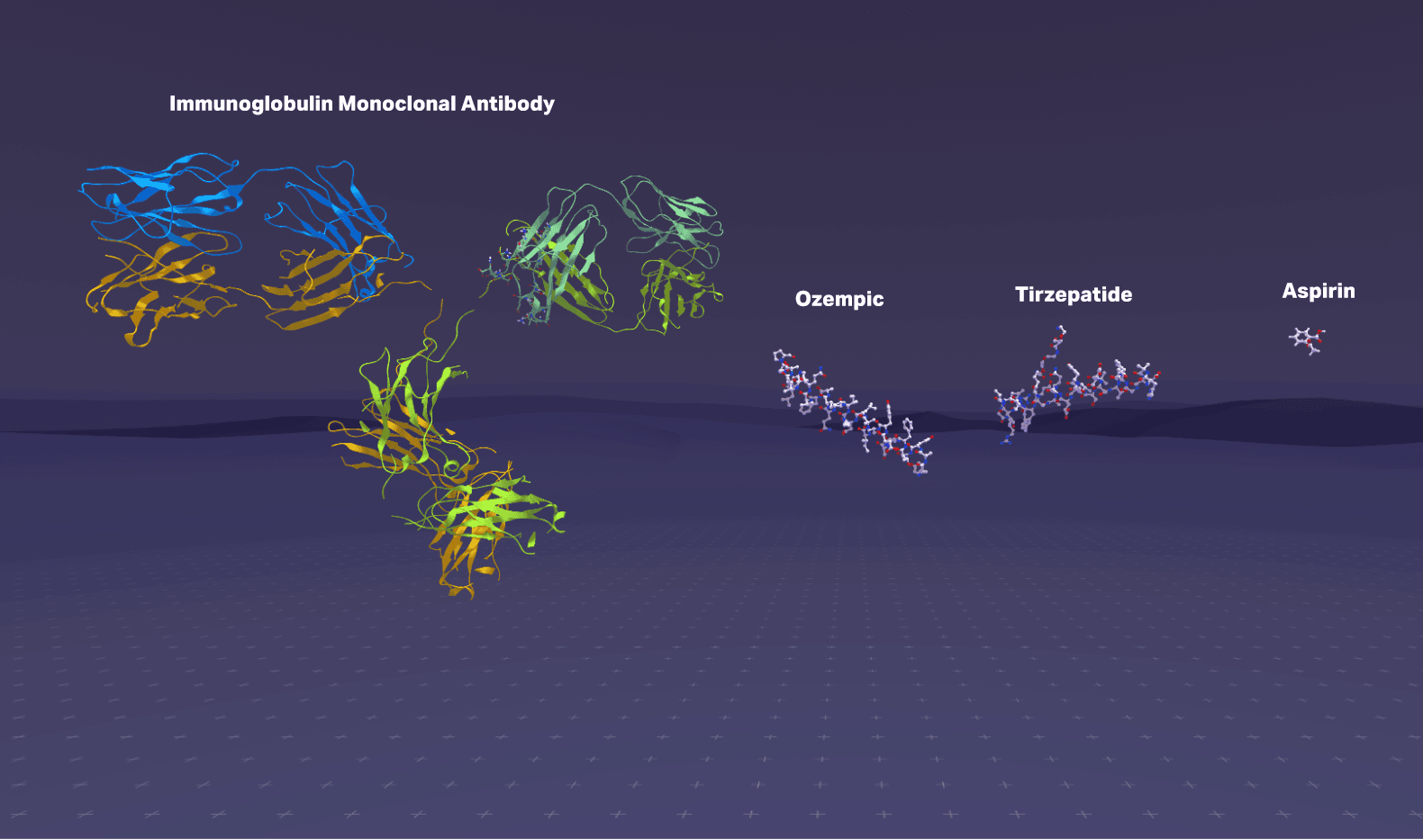

Then I told them something that seemed to genuinely surprise them: the difference between the Ozempic they'd heard about, the small molecule drugs in their medicine cabinet, and the monoclonal antibodies treating cancer patients comes down to atom count.

That's it. How many atoms are chained together.

Their reaction wasn't confusion. It was recognition. Like something that had been fuzzy suddenly snapped into focus.

The Problem With Hand-Wavy Medicine

Here's what struck me about that conversation: these were intelligent, successful people who make complex decisions for a living. They understood market dynamics, risk profiles, competitive moats. But when it came to the actual thing driving a trillion-dollar valuation, their mental model was essentially: "hand-wavy breakthrough does hand-wavy thing, therefore I lose weight."

And honestly? That's not their fault. It's how we talk about medicine, health, and medicine.

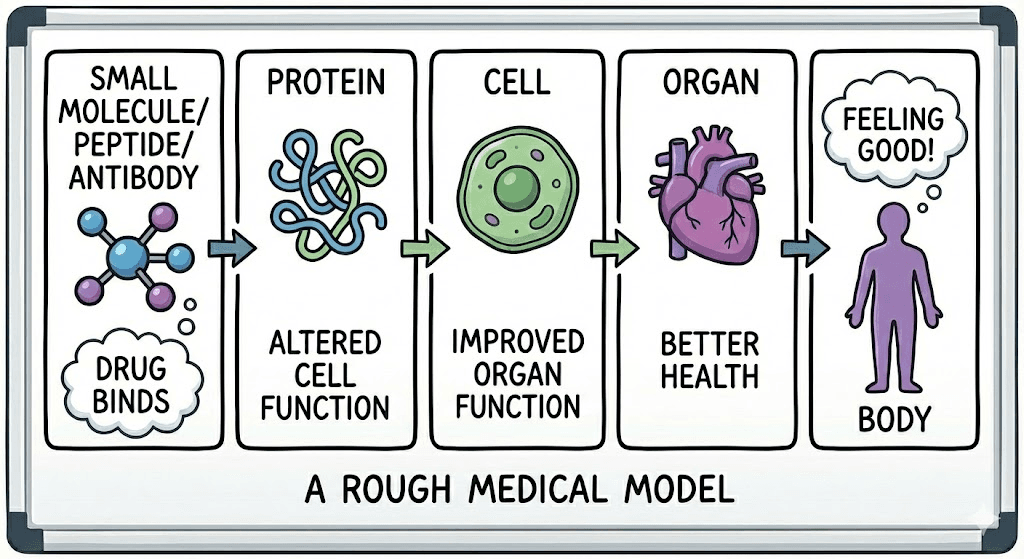

We say "GLP-1 agonist" without explaining that it's a specific molecular structure, a chain of amino acids folded into a precise 3D shape, that fits into a receptor on your cells like a key into a lock. We say "targets the glucagon pathway" without often conveying that this means a physical object (a molecule) is literally binding to another physical object (a protein) and triggering a cascade of events inside a cell that eventually translates into you feeling less hungry.

It's all real. It's all physical. It's all happening at a scale we can't see, but absolutely can visualize.

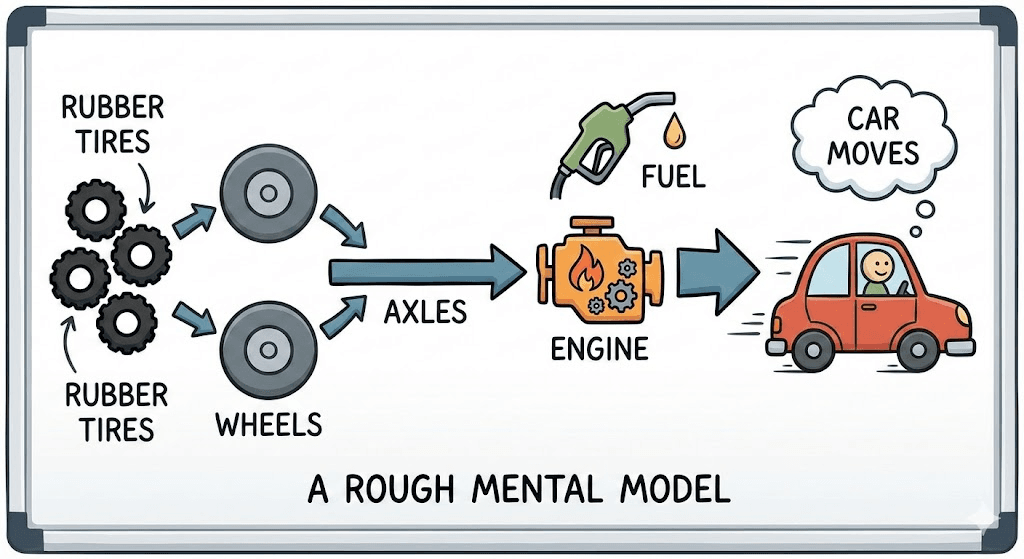

Think about how most people understand cars. They don't know gear ratios or combustion thermodynamics. But they have a rough mental model: rubber tires connect to wheels, wheels connect to axles, axles connect to an engine, engine burns fuel, car moves. That's enough to understand why a flat tire matters, why you need gas, why the engine overheating is bad.

We don't have that for medicine. When someone without a scientific background takes Ozempic, they don't picture a 31-amino-acid chain binding to a receptor on their intestinal cells. They don't visualize the conformational change that triggers intracellular signaling. They just know "it works for weight loss."

The gap between those two levels of understanding (between hand-wavy abstraction and tangible mechanism) is what we think about constantly. Because closing that gap isn't just about education. It's about how we design better drugs, communicate their value, and make informed decisions about our own biology.

Everything Is Atoms, and Atoms Are 3D

To make this concrete, when we talk about drug categories, I like to think we're really talking about size: how many atoms, how they're arranged, how much space they occupy.

Small molecules are tiny. Aspirin is about 21 atoms. These can slip through cell membranes easily, which is why you can swallow a pill and have it work throughout your body. But their small size limits how precisely they can interact with large, complex protein targets.

Peptides are chains of amino acids linked by amide bonds. Semaglutide (Ozempic) is 31 amino acids, maybe 500 atoms total. Tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is 39 amino acids. These are large enough to bind protein targets with high specificity, but small enough to be synthesized and modified with precision.

Antibodies are massive: around 20,000 atoms, roughly 150,000 Daltons. They're incredibly specific, which is why they're used for targeted cancer therapies, but their size means they can't enter cells and are expensive to manufacture.

Here's the thing: all of these exist in three-dimensional space. They fold, they flex, they rotate. A peptide isn't a string of letters (HAEGTFTSDV...). It's a physical object with a shape. And that shape determines everything: whether it binds to its target, how tightly, for how long, what side effects it causes.

When I explain this to people and they finally see it (when the abstraction becomes tangible), something clicks. "Oh, it's like... a thing. A physical thing. That does a physical thing to another physical thing."

Yes. Exactly.

And yet that's exactly where drug design happens now.

Tirzepatide isn't effective because someone discovered it in a plant. It's effective because researchers designed a specific sequence of amino acids, optimized the chain length, modified certain residues to improve stability, and engineered the 3D fold to bind two different receptors simultaneously. Every decision was made at the nano scale level.

This is the transition happening in medicine: from discovering molecules to engineering them. From finding things that work to designing things that work. And that transition requires a different way of seeing.

The Atomic Precision Revolution

Three shifts are driving this:

1. We've moved from discovery to design.

For most of pharmaceutical history, drug discovery was trial and error. Screen thousands of compounds, see what sticks, and optimize.

That era is ending. Today we have AlphaFold predicting protein structures with near-perfect accuracy, computational chemistry modeling molecular interactions before synthesis, cryo-EM revealing exactly how drugs bind to targets, and solid-phase peptide synthesis allowing us to build custom amino acid chains on demand.

We're not just finding molecules anymore. We're designing them, atom by atom, with clear intent.

This is something we've been tracking closely at Nanome. Nearly 6 years ago, we published a video breaking down semaglutide and the GLP-1 mechanism, showing the actual molecular structure, how it binds, why it works. This was years before Ozempic became a household name. At the time, few people outside pharma cared about peptide visualization. What's changed isn't the science. It's the recognition that this level of understanding matters.

2. The results are already transforming medicine.

GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide and tirzepatide are peptides that mimic natural gut hormones. They slow gastric emptying, regulate insulin and glucagon, and act on the brain to reduce appetite. Eli Lilly's tirzepatide alone generated over $10 billion in sales in 2024 and just pushed Lilly past a $1 trillion market cap.

But GLP-1s are just the beginning. Antibody-drug conjugates combine antibody targeting precision with small molecule killing power. PROTACs hijack the cell's own protein disposal system to eliminate previously "undruggable" targets. mRNA vaccines proved they could be developed at pandemic speed.

Each represents a different point on the molecular weight spectrum. All share one thing: they were designed with atomic precision to do something previously impossible.

3. The old categories are breaking down.

We now have cyclic peptides with small molecule-like oral bioavailability, stapled peptides with enhanced stability that bridge the peptide-protein gap, and macrocycles that span categories entirely.

Instead of asking "should we make a small molecule or a biologic?", drug designers now ask: "What's the optimal molecular architecture to hit this target with the right pharmacokinetics, stability, and safety profile?"

Sometimes that's 20 atoms. Sometimes it's 20,000. Increasingly, it's something in between that didn't exist in nature and wouldn't have been possible to design a decade ago.

Closing the Tangibility Gap: Why The Interface Matters

Here's why I think all of this matters beyond the science.

When people can't visualize what's happening at the molecular level, they can't really evaluate claims about medicine. They can't distinguish between genuine breakthroughs and marketing hype. They can't understand why one drug costs $1,000/month and another costs $10. They can't participate meaningfully in decisions about their own health.

The tangibility gap isn't just an education problem. It's a communication problem. And it's one that gets harder as molecular design gets more sophisticated.

This is fundamentally why we built Nanome. Our XR molecular visualization platform exists because we believe the most important insights in drug discovery happen when you can actually see molecular structures in 3D, at atomic resolution, and interact with them spatially. When a medicinal chemist can reach out and rotate a peptide, zoom into a binding pocket, show a colleague exactly where a modification changes the interaction surface, that's when abstraction becomes tangible.

That's where the actual insight occurs. That's when abstraction becomes tangible.

We've watched drug discovery teams using Nanome cut weeks from lead optimization cycles because design discussions happen directly on the structures instead of over static slides. The limiting factor in molecular design isn't data anymore (we have petabytes of structural data). The limiting factor is interface. Whether you can actually manipulate what you're trying to build.

When you can see the thing you're building at the scale you're building it, you make different decisions.

Our XR molecular visualization platform exists because the most important insights in drug discovery happen when you can actually see molecular structures in 3D, at atomic resolution, and interact with them spatially. When the abstraction becomes tangible, everything changes: how fast you iterate, how clearly you communicate, how confidently you decide.

The Future Is Atomically Precise

Back at that networking event, after we'd talked through peptides and atom counts and why molecular shape matters, I decided to push a little further.

"You know the H100?" I asked. The NVIDIA chip powering the AI revolution. Of course they knew it.

"It's built on a 4-nanometer process. A single transistor gate is about the width of four aspirin molecules lined up side by side."

I watched their expressions shift. The same look of recognition from earlier, but deeper now.

The chip driving every AI breakthrough they'd been reading about, every LLM, every billion-dollar compute cluster, it exists at the same scale as the molecules in their medicine cabinet. The transistors switching on and off billions of times per second are operating at the same level of atomic precision as the peptides regulating their metabolism.

And suddenly they saw what I see every day:

Everything is made of molecules. Everything that matters in the future (computing, medicine, materials, energy) is converging on molecular-scale design. The companies that win will be the ones that can engineer at this level with precision and intent.

The atomic revolution isn't coming. It's here. It's in the chips powering AI. It's in the peptides treating obesity. It's in the antibody-drug conjugates targeting cancer cells. It's in the mRNA vaccines that responded to a pandemic in months instead of years.

The question isn't whether the future will be built at atomic scale. It's whether we'll have the tools to see it, design it, and communicate it clearly.

That's what Nanome is for. We're building the interface to design the future.