20 years and a vaccine for Lyme Disease is still in the works, but structural biology has another trick up its sleeve: Antibody Prophylaxis!

Ticks are notorious for their pesky bites, but there's a more serious concern associated with them: Lyme Disease. It's the most common tick-borne infection in the United States, with over 30,000 cases reported each year. If left untreated, it can lead to serious complications in joints, heart, and nervous system.

How do ticks spread Lyme Disease? Blacklegged ticks feed on the blood of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. They hide in grass, sensing body heat and waiting for the chance to climb aboard a passing host. Then, like a vampire, the tick will pierce its victim’s skin and begin drinking its victim’s blood. Any bloodborne infections carried by the host will pass into the tick, so when the tick feeds on to its next victim, it can transmit the infection. Lyme Disease is one of the more harmful infections spread by ticks and is caused by bacterium or (Borrelia burgdorferi in North America, or B. garinii and B. afzelii in European and Asian countries.)

Reported cases of Lyme Disease in the USA, 2018. Source CDC.

Reported cases of Lyme Disease in the USA, 2018. Source CDC.

Unfortunately, there's no cure for Lyme Disease, and no human vaccine or monoclonal antibody therapy is currently available on the market. Efforts to develop a new vaccine have been ongoing for two decades, and several vaccines are currently in development and undergoing clinical trials.

“The only therapeutic option available if you do get bitten by a tick and are infected in the first 48 hours or so, is to get a regimen of antibiotics that can clear the bacteria and mitigate or prevent the disease.” says Dr. Michael Rudolph, a scientist working on Lyme Disease at the New York Structural Biology Center.

Prevention is better than cure: therapeutic antibodies

However, scientists like Dr. Michael Rudolph and his collaborators at MassBiologics and the Wadsworth Center have been exploring a different route than vaccination: antibody prophylaxis. Essentially, this means using antibodies to prevent infection before it occurs.

When a tick latches onto someone, it takes at least 36 hours to pass along the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. This provides a window of time for antibodies to get into the tick's gut and block transmission of the bacterium.

If antibodies that specifically recognise B. burgdorferi are administered at the beginning of tick season, they act like a prophylactic to Lyme disease. So, if a subject has antibodies at the moment of the bite, infection can be prevented.

What’s the difference between vaccines and antibody prophylaxis?

Vaccines use inactivated viruses or bacteria to stimulate an immune response, priming the human body to fight off future exposure. They help prevent a future illness, but do not treat the illness itself. By contrast, antibodies identify and attack a specific disease causing organism. If you already have antibodies in your system at the time of being exposed to a disease organism, then they can prevent disease from taking root.

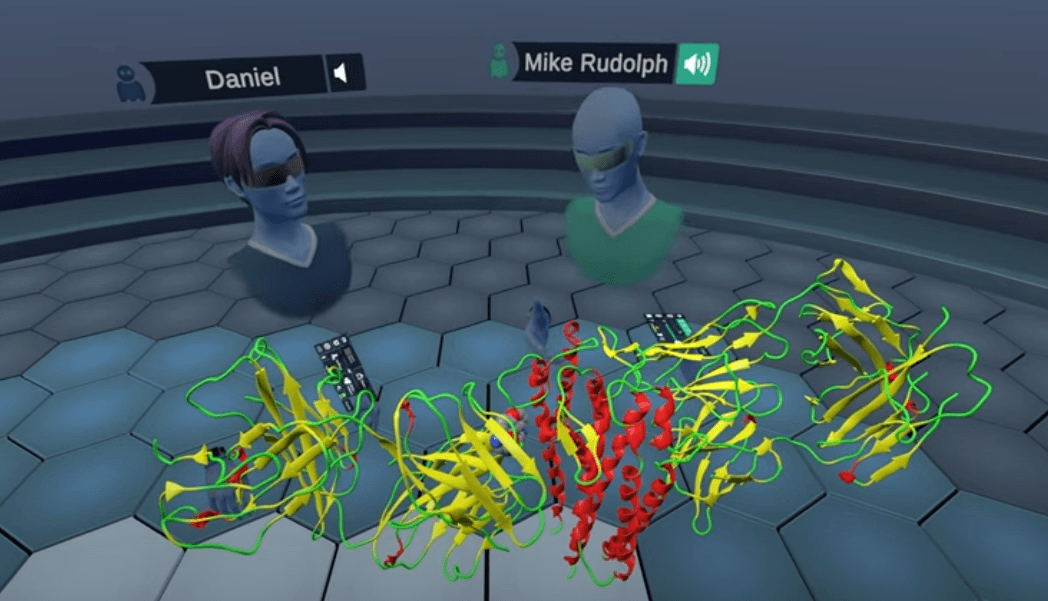

Antibodies in VR: Therapeutic Antibodies Against Lyme Disease w/ Dr. Mike Rudolph - NYSBC on YouTubeView the full video here.

Antibodies in VR: Therapeutic Antibodies Against Lyme Disease w/ Dr. Mike Rudolph - NYSBC on YouTubeView the full video here.

Secret powers of antibodies explained

Dr. Rudolph's team has been studying the outer surface proteins (Osp) of the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, which are responsible for its virulence and immune evasion. If you have antibodies against those, chances are that you are not going to develop Lyme disease.

Dr. Rudolph is using structural biology techniques like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy to study the three-dimensional structure of Osp proteins when they are bound to protective antibodies. By understanding how the immune system recognizes these proteins, researchers can design more effective vaccines and therapies for Lyme disease.

With the help of virtual reality tools like Nanome, Dr. Rudolph's team has explored the structures of Osp proteins in complex with protective antibodies. They've discovered the critical regions of Osp proteins recognized by protective antibodies and how they bind tightly together.

Antibodies in Nanome

Our team had the pleasure to meet Dr. Rudolph in Nanome and explore these structures in virtual reality.

We started with OspA bound to the human antibody fragment 227-1 that is now undergoing clinical trials (PDBid 7JWG).

With the ‘Antibody Representation’ plugin we highlighted the Complementarity-determining Regions (CDRs) of the antibody fragment and immediately saw that OspA strands 4-9 are the ones recognised by 227-1.

OspA bound to the human antibody fragment 227-1 in Nanome

OspA bound to the human antibody fragment 227-1 in Nanome

That’s good news! We know that that region is conserved across different Borrelia variants, which means that antibody 227-1 has the potential to be protective against multiple strains. Plus, we visualized the intricate network of interactions between 227-1 and OspA with the Chemical Interaction plugin, which helped to explain the tight binding.

We then pulled up another outer surface protein OspC, bound to the antibody fragment B5. Even though B5 was characterized years ago, until now, we didn’t know where it binds to OspC.

During our VR session, Dr. Rudolph solved and presented for the first time the characterization of the epitope recognised by the protective antibody B5.

Comparing Lyme structures in Virtual Reality

Comparing Lyme structures in Virtual Reality

We compared OspC-type A structures to OspC-type B with Superimpose Proteins, noting how specific residues on the epitope binding region were not conserved, thus preventing the cross reactivity of B5.

Moving Forward

By gaining a deeper understanding of the interactions between protective antibodies and Osp proteins, Dr. Rudolph's team hopes to aid in the rational design of Osp-based vaccines and therapeutics. While a vaccine for Lyme disease may not exist yet, structural biology is providing valuable insights and potential solutions for prevention and treatment.

View the full in-VR video of Nanome scientists exploring OspA and OspC antibodies complexes here.

Additional Resources:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8159683/

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.11.28.518297v1

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36000876/

Lyme vaccines in clinical trials:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Lyme+Disease&term=vaccine&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search